Researchers from the Tokyo Institute of Technology and the National Institute for Fusion Science have made a pivotal discovery regarding the chemical interaction between high-temperature liquid tin (Sn) and a structural material known as reduced activation ferritic martensitic (RAFM) steel—an essential candidate for fusion reactor construction.

Their findings could help improve cooling systems in future fusion reactors, a key component for sustainable energy generation.

Fusion energy, seen as a potential solution for producing clean, zero-carbon power, is being pursued worldwide, with major international collaborations like the ITER project, as well as private sector initiatives. ITER was initially called the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor.

The primary appeal of fusion lies in its use of deuterium and tritium—fuels derived from seawater—that produce no greenhouse gas emissions. A critical challenge in these reactors is managing the intense heat generated during the fusion process, especially within the plasma-facing components such as the divertor.

The Role of Divertors in Fusion Reactors

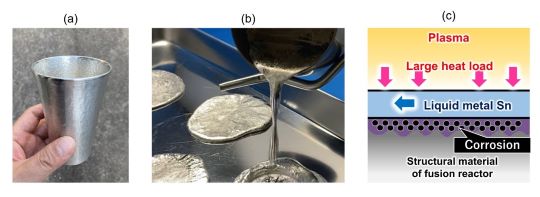

A fusion reactor’s divertor plays a crucial role in maintaining plasma purity by removing impurities and heat. Traditional divertors rely on solid materials like tungsten, which are in direct contact with the plasma and require efficient cooling to withstand extreme heat levels—similar to the temperatures experienced by spacecraft re-entering the Earth’s atmosphere. While these solid divertors are in use in projects like ITER, researchers are increasingly considering liquid metal divertors for their superior cooling properties.

Tin (Sn), a relatively low-melting-point metal at 232 °C (450 °F), has been proposed as a potential coolant due to its ability to remain liquid at high temperatures. Tin also has a low vapor pressure compared to other liquid metals, making it less prone to evaporation.

This property could make liquid tin an ideal coolant for fusion reactors, where it would help protect structural materials from the intense heat of the plasma.

The Corrosion Challenge

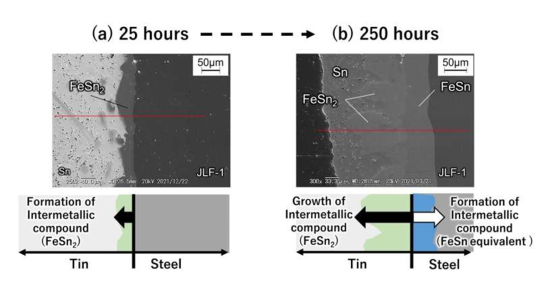

However, the high reactivity of liquid tin at elevated temperatures poses a significant challenge. Specifically, when RAFM steel—composed mainly of iron, chromium, and tungsten—comes into contact with liquid tin, corrosion occurs quickly. This is due to the reaction between iron in the steel and the tin, which forms intermetallic compounds (such as FeSn2), leading to material degradation.

While chromium and tungsten in the steel do not react as readily with tin, the presence of iron accelerates the corrosion process, especially at temperatures above 500 °C (932 °F).

In their experiments, researchers exposed RAFM steel to liquid tin at 500 °C for varying lengths of time. After just 25 h, the steel began forming intermetallic compounds on its surface, and after 250 h, the material showed significant corrosion.

At higher temperatures, such as 600 °C (1,112 °F), corrosion worsened, with tin infiltrating the steel’s microstructure, further weakening the material.

Associate Professor Masatoshi Kondo of the Tokyo Institute of Technology, who leads the research team, explains, “Although liquid metal tin is an excellent coolant with a variety of properties, it has the drawback of corroding structural materials. By clarifying the corrosion mechanism, we hope to promote the use of liquid metal tin not only for fusion energy but also for solar thermal power plants.”

Identifying Solutions: Oxides to the Rescue

To mitigate this issue, the researchers turned their attention to the possibility of preventing corrosion by coating the steel with oxide layers prior to exposure to liquid tin. The team tested iron oxide (Fe2O3) and chromium oxide (Cr2O3) to see if these materials would be more resistant to corrosion.

Their findings were promising. When iron oxide sintered materials were immersed in liquid tin at 500 °C, they experienced only minimal corrosion, with the tin penetrating the material’s pores to form a very thin reaction layer. This reaction was just a fraction of the corrosion observed in the uncoated steel, suggesting that oxide coatings could significantly reduce the reactivity of steel with tin. Similarly, chromium oxide sintered materials showed a similarly low rate of corrosion.

These results indicate that using oxides, such as iron and chromium oxides, can be an effective strategy to protect steel from the damaging effects of high-temperature liquid tin.

Next Steps and Future Implications

The research conducted by Masatoshi Kondo and his team is a major step toward understanding the complex interaction between liquid tin and fusion reactor materials. According to Kondo, while liquid tin offers excellent cooling potential, its corrosive nature needs to be carefully addressed.

By exploring corrosion mechanisms and identifying suitable materials, the team aims to develop durable, corrosion-resistant materials that will allow liquid metal cooling systems to become a viable option in future fusion reactors.

Looking ahead, the researchers are collaborating with the Oak Ridge National Laboratory in the United States to investigate how fusion reactor radiation could further influence corrosion dynamics. This research not only has the potential to enhance fusion reactor designs but also may offer insights into other energy systems, such as solar thermal power plants, where liquid metal coolants are increasingly being explored.

In the long run, overcoming the challenges of corrosion in liquid metal cooling systems could be key to achieving reliable and efficient fusion energy, advancing the global transition to a carbon-neutral society.

Source: Institute of Science Tokyo, www.titech.ac.jp/english.

Editor’s note: This article first appeared in the January 2025 print issue of Materials Performance (MP) Magazine. Reprinted with permission.