A recent U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) (Washington, DC) report1 found moderate or severe corrosion likely affects metal components inside diesel fuel underground storage tanks (USTs), which, unmonitored, could create UST system failures leading to groundwater contamination.

The study found that, while less than 25% of UST owners were aware of corrosion prior to inspection, 83% of USTs studied showed moderate to severe corrosion problems.

“Corrosion inside USTs can cause equipment failure by preventing the proper operation of release detection and prevention equipment,” the EPA says in its report.

“If left unchecked, corrosion could cause UST system failures and releases, which could lead to groundwater contamination,” the agency adds.

Underground tank releases have historically been a leading cause of U.S. groundwater contamination, the EPA says. Groundwater is a source of drinking water for almost half of the U.S. population.

Background

UST owners began reporting rapid and severe corrosion of their metal components to industry service providers in 2007, the EPA says, noting that several changes to U.S. fuel supply and fuel storage practices have occurred since the mid-2000s.

To examine these apparent corrosion issues, the EPA began its research in 2014 to understand the severity of the problems, as well as to identify predictive factors between UST systems with corrosion issues and UST systems that are relatively free of the problem.

“The objective for the research was to develop a better understanding of potential risks to human health and the environment caused by the evolving corrosion problem in USTs storing diesel fuel,” the agency says.

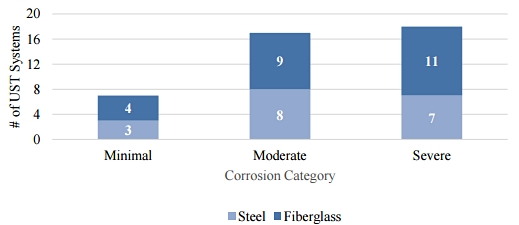

In January and February 2015, the EPA conducted on-site inspections of 42 operating UST systems at 40 sites across the United States. Of these UST systems, 24 had fiberglass tanks and 18 had steel tanks.

Field teams documented the conditions of the UST systems with in-tank video cameras and photos so they could later assign a category of corrosion coverage to each system. The field teams collected samples of the vapor, fuel, and aqueous phases, if present, from each of the tanks. The teams also gathered information from each UST owner about the storage history, operation, and maintenance practices of each system.

Findings

The EPA then analyzed the vapor, fuel, and aqueous phase samples, while three assessors reviewed the videos of each UST and categorized the USTs by the extent of corrosion judged to be present (minimal, moderate, or severe).

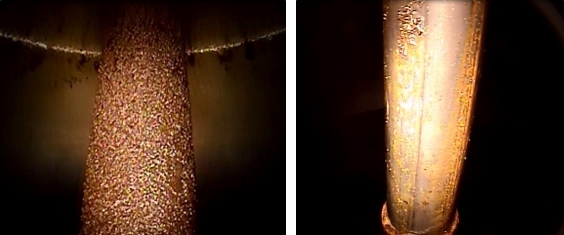

The agency says its observations suggest that corrosion may be commonly severe on metal surfaces in the upper vapor space (Figure 1) of UST systems. The EPA adds that before 2007, this area was not known to be prone to corrosion.

“The major finding from our research is that moderate or severe corrosion on metal components in UST systems storing diesel fuel in the United States could be a very common occurrence,” the EPA says.

“It appears from our research that corrosion inside of UST systems could result in an increased chance of releases of fuel to the environment and subsequent groundwater contamination,” the agency adds.

The corrosion was geographically widespread and affects UST systems with both steel tanks and fiberglass tanks (Figure 2), and it poses a risk to most internal metal components, the EPA says.

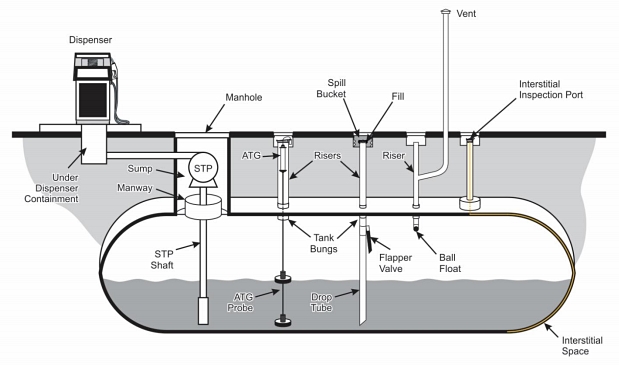

Across the samples, the EPA observed corrosion occurring on all types of UST system metal components (Figure 3), including submersible turbine pump shafts, automatic tank gauge probe shafts, risers, overfill equipment such as flapper valves and ball valves, bungs around tank penetration, inner walls of tanks, and fuel suction tubs.

“Corrosion of some metal components could hinder their proper operation and possibly allow a release of fuel to occur, or continue unnoticed,” the EPA says.

Because of how new the problem appears to be, the EPA says it has very little verifiable data about how equipment functionality and integrity are being affected by this corrosion in USTs. At the moment, the EPA says it has heard anecdotes of functionality failures of release prevention equipment and leak detectors, as well as failures of metal walls resulting in leaks into secondary containment areas.

“However, that information should become more available as owners become more aware of the findings of our research, and corrosion in USTs storing diesel becomes more visible,” the EPA says, adding that even if fuel is not released into the environment, severe corrosion still poses significant concerns for UST owners.

Multiple Factors Contribute to Corrosion

The EPA says that its data and analysis could not pinpoint a single cause for the corrosion that UST owners began reporting in 2007. Rather, it appears that multiple underlying factors and corrosion mechanisms could be contributing.

One such factor is microbiologically influenced corrosion (MIC). The agency notes that prior research suggests reduced sulfur in diesel could be allowing microbial life to proliferate in ultra-low sulfur diesel tanks and, through MIC, cause corrosive conditions that are less possible in USTs storing low-sulfur diesel.

The EPA believes that following enhanced maintenance practices can minimize MIC risks by either reducing the bacterial populations or preventing an environment where microbial life can thrive.

The agency notes that its Office of Research and Development hypothesized that biofuel components in diesel, such as ethanol and biodiesel, could be providing the energy source for microbial populations. The research shows that ethanol was present in 90% of the 42 UST samples, suggesting that the cross-contamination of diesel fuel is likely the norm.

Statistically, the EPA says that the particulates and water content in the fuel were closest to being significant predictive factors for metal corrosion. But the researchers caution that causation cannot be discerned based on this study.

Moving forward, the EPA says it is continuing to work collaboratively with partners in the UST community, industry, and scientific experts on additional laboratory research on the cause of corrosion.

Outlook

While the EPA says it cannot project the actual percentage of USTs storing diesel in the United States that are affected by corrosion, it is alerting all owners of those USTs about the risks and advising them to check their systems for corrosion and take steps to ensure proper operability.

“EPA’s notification recommends owners check inside their tank systems and further investigate the condition of their diesel fuel tanks,” the EPA says. “Owners’ awareness and early actions could help protect them from higher repair costs and help protect the environment from contamination from releases.”

The EPA’s UST Web site provides specific information on actions tank owners can take to minimize corrosion and the associated risks.

Reference

1 “Investigation of Corrosion-Influencing Factors in Underground Storage Tanks with Diesel Service,” U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Office of Underground Storage Tanks, EPA 510-R-16-001, July 2016.