A major natural gas leak in 2015 at a Southern California storage facility was caused by the microbial corrosion of well equipment, according to a new independent report conducted by Blade Energy Partners (Frisco, Texas, USA). The analysis report1 was first ordered in January 2016 to help identify the root cause of the leak, which began on October 23, 2015.

For the study, Blade was commissioned by the California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC) (San Francisco, California, USA), in consultation with the California Department of Conservation’s Division of Oil, Gas, and Geothermal Resources (DOGGR) (Sacramento, California, USA) and the U.S. Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA) (Washington, DC, USA).

The organizations say the report’s findings will be used to supplement parallel investigations that are underway by CPUC and DOGGR.

Findings on the Leak

The Aliso Canyon facility is comprised of dozens of underground caverns, which were previously filled with oil before they were emptied decades ago. Since then, they have been used to store natural gas to supply the surrounding area.

On October 23, 2015, an outer 7-in (17.8-cm) well casing located ~500 ft (152.4 m) underground ruptured, owing to microbial corrosion from the outside due to contact with groundwater, according to the analysis report. The microbial induced corrosion caused metal in the casing to thin. Hours later, a complete separation of the casing occurred. The damaged portion of the well was difficult to access and could not initially be seen with a camera.

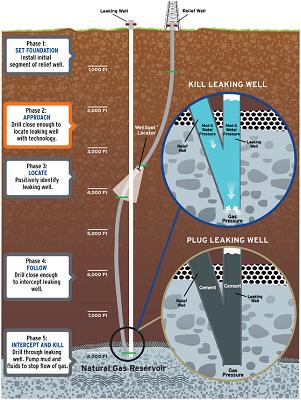

Well control and prevention specialist Boots & Coots, now owned by Halliburton (Houston, Texas, USA), was brought in within two days of discovering the leak to help mitigate the release. In December, a relief well was constructed to intersect with the damaged well, with cement pumped in to permanently seal off the original well. The leak was not completely stopped until February 11, 2016.

Well control and prevention specialist Boots & Coots, now owned by Halliburton (Houston, Texas, USA), was brought in within two days of discovering the leak to help mitigate the release. In December, a relief well was constructed to intersect with the damaged well, with cement pumped in to permanently seal off the original well. The leak was not completely stopped until February 11, 2016.

According to the California Air Resources Board (CARB) (Sacramento, California, USA), 109,000 metric tons of methane were released into the atmosphere over the leak’s five-month duration. CARB notes that methane’s warming potential is up to 84 times that of carbon dioxide (CO2).

The analysis report says Southern California Gas Company (SoCalGas) (Los Angeles, California, USA), which owns the storage facility, had not conducted detailed follow-up inspections or analyses after previous leaks at the site. According to Blade, more than 60 casing leaks at Aliso Canyon had been identified before the October 2015 incident, going back to the 1970s, but no failure investigations were conducted by the site owner.

Moreover, according to the report, the owner “lacked any form of risk assessment focused on well integrity management…and lacked systematic processes of external corrosion protection and a real-time, continuous pressure monitoring system for well surveillance.”

Regulatory Decisions

Since the leak, CPUC and DOGGR say they have taken aggressive steps to prevent a similar leak from occurring again, including DOGGR’s stringent new regulations for all underground gas storage reservoirs.

“Enacted immediately after the leak began and made permanent on October 1, 2018, the regulations ensure that no single point of failure in a well can cause a release of gas into the atmosphere,” CPUC says. “The regulations have been cited by [PHMSA] as some of the strongest in the nation. Among the requirements are robust well construction standards, mechanical integrity testing to detect a problem before it occurs, real-time pressure monitoring, and a mandate that gas production and withdrawals can only occur through production tubing, rather than through both the tubing and the protective casing.”

In addition, CPUC and DOGGR have issued other directives to SoCalGas, both immediately after and since the leak. Specifically, the organizations required the owner to complete a rigorous comprehensive safety review before reopening. “Each well was required to either pass a battery of tests to potentially be eligible to resume gas injection or be taken out of operation and isolated from the reservoir,” CPUC notes. “The utility was also ordered to conduct air sampling surveys of the neighborhoods surrounding the storage field, and to equip active wells with real-time air pressure monitors.”

CPUC and DOGGR’s parallel investigations are focused on overall well and field operations, with reports expected to be completed by the end of 2019. Technical expertise for those will be provided by the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley, California, USA) and the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (Livermore, CA, USA), as well as Sandia National Laboratories (Albuquerque, New Mexico, USA).

Owner’s Response

In its own statement2 issued following the report’s release, owner SoCalGas says the report confirms that it did not violate well or safely regulations that existed at the time.

“The Blade report confirms SoCalGas complied with gas storage regulations in existence at the time of the leak and that the related compliance activities conducted prior to the leak did not find indications of a casing integrity issue,” the company says.“In Blade's opinion, there were measures, though not required by the gas storage regulations at the time, that could have been taken to aid in the early identification of corrosion and that, in their opinion, would have prevented or mitigated the leak.”

Earlier in the year, a Los Angeles court approved a $119.5 million settlement related to the leak between the owner and CARB. A significant portion of that money will go to build methane digesters at 12 dairy farms in California’s San Joaquin Valley, with another portion going to the construction of conditioning facilities and pipelines to allow the Aliso Canyon system to receive biomethane generated by cattle in the valley’s dairies.

CPUC and DOGGR say that their initial assessment is that measures taken to date do address the Blade report’s findings and recommendations. They add that the analysis “will be used to further improve regulations and overall gas storage facility oversight practices as appropriate.”

CPUC also notes that it has a proceeding underway to determine the feasibility of minimizing or eliminating the use of Aliso Canyon, while still maintaining energy and electric reliability for the Los Angeles region. Further meetings on that topic are planned in the months ahead.

Source: CPUC, cpuc.ca.gov.

References

1 “Root Cause Analysis for Aliso Canyon Finalized; California to Continue Strengthening Safeguards for Natural Gas Storage Facilities,” California Public Utilities Commission Press Release, May 17, 2019, http://docs.cpuc.ca.gov/PublishedDocs/Published/G000/M292/K947/292947433.PDF (June 18, 2019).

2 “SoCalGas Issues Statement on Blade's Analysis of Aliso Canyon Well Failure,” Sempra Energy Newsroom, May 17, 2019, https://www.sempra.com/socalgas-issues-statement-blades-analysis-aliso-canyon-well-failure (June 18, 2019).